Part 1: Observation

We have recently adapted the style of documentation called Floorbooks: Talking and Thinking Floorbook Approach, which was created by Claire Warden to give educators a tool to consult and co-create documentation with children.

This approach allows children and educators to make their thinking, theories, values and learning visible. This collaborative pedagogical approach allows educators to slow down and truly listen to children and base their responsive planning on the unique interests of the children in their programs. These blank canvases allow children and educators to engage in critical reflection together, this reflection propels the responsive programming further. As noted by the Ministry of Education, “Children learn through questioning and testing theories in their play. In the same way, we encourage educators to be researchers, to try new ideas and test theories” (pg. 20, 2014c.)

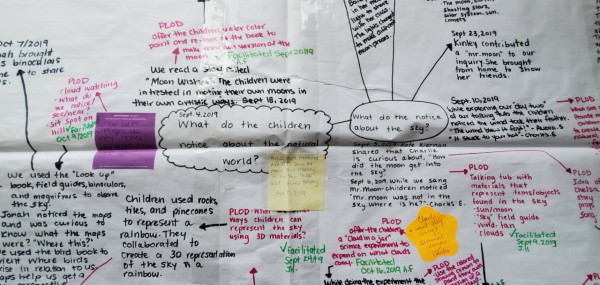

We use our Floorbook to co-create our observations together with the children. We offer the children the opportunity to have regular and repeated access to this visual representation of the thinking as a means to engage in group social recall where children can write, draw, and reflect on photographs on themselves engaging in meaningful experiences with their peers. Below is an excerpt from an ongoing investigation that our preschool children have been engaged in from September 2019-March 2020.

Where it all began…

The original inquiry or theory we were curious to investigate with the children was based on observations about the sky and the natural world. Once I returned from our week together in Kitchener, I offered some of the music to the children that we learned together and one of the classroom favourites was “Mr. Moon.” The children would spend days observing, noticing, and growing more curious about the sky and we wondered:

- What do the children already know about the sky?

- What are the children curious about the sky?

- What is our relationship with the sky?

- What are the new ways we can observe the natural world?

- How can children use creative materials to represent their theories and what they know in creative ways?

As a team, we co-create a mapping system to web out our observations and “Possible Lines of Development.” This served as a tool to make our observations of the children visible to families as well. We were pleasantly surprised to see the high amount of parent engagement and collaboration. Parents began bringing in books, resources, and ideas to extend and enrich the children’s learning. They shared different theories that the children would discuss at home and this offered us an excellent springboard to offer the children a vast array of responsive planning experiences.

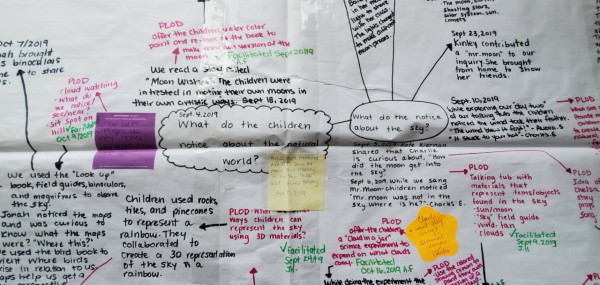

However, this method is a great tool to use to critically examine your own program. We have created a resource in the back of each of the Floorbooks that allows you to make connections to each page and experience to our Program statement, and How Does Learning Happen: Ontario’s Pedagogy for the Early Years. With this tool, we were able to look for gaps in our programs and the ways in which we can offer a program with more breadth. This is was also a great tool that parents were able to see the connections between our play-based and nature-based program to specific learning outcomes. As a licensed child care center, this resource also proved to be helpful when we had our annual licensing inspection from the Ministry of Education. Our program advisor noted that this tool proved to make the reflective process of educators visible and children’s thinking, theories, and engagement visible. Overall, I feel this pedagogical approach allows educators to represent the 100 languages of how children think, learn, and communicate.

Here is an excerpt from our documentation processes that are found in our preschool classroom Floorbook based on the inquiry: What do the children notice about the sky?

In this form of documentation, both the educators and the children’s voices are represented which offers children, families, educators, and other collaborators to reflect and engage with the work over multiple experiences and through a variety of different lenses.

This method brought value to the children’s work and was another way we showed our view that the children’s ideas held value in our learning community. By respecting and making children’s work published in a classroom Floorbook, we are able to live in the value that the children’s ideas are of value and drive the direction of our programs. It represents the value that children are competent and capable of complex thinking.

“Pedagogical documentation is about more than recording events. It is a means to learning about how children think and learn. As suggested by Carlina Rinaldi, it is a way of listening to children, helping us to learn about children during the course of their experiences and to make this learning visible to others for interpretation. And, it encourages educators to be co-learners alongside both children and their families” (Ministry of Education, pg. 21, 2014c.)

The observation of this work brought new questions to our team:

- What role do maps have in showing us new perspectives of the world?

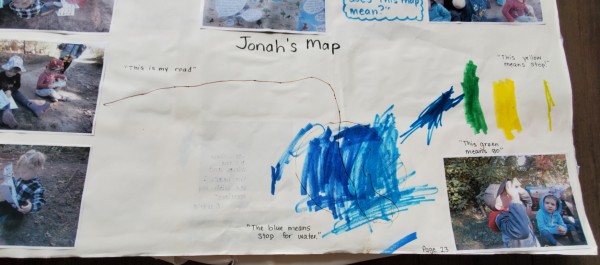

- How do children naturally use mapping to make their thinking and theories visible?

- What new tools can we offer children to nurture their own observation skills?

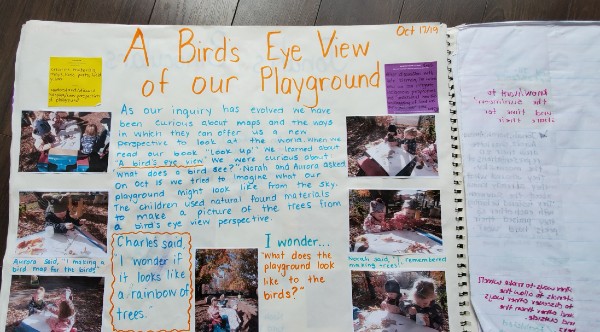

- How can we support children’s understandings of a new perspective of a ‘birds eye view’ of the world?

- How do maps offer us a way to understand the land we use from the past, present and future? How can we integrate an understanding and respect for the original caretakers and Indigenous peoples of the land we use each day?

These questions offered us a new springboard or direction to drive the new experiences and responsive programming experiences we offered the children in our program. These questions also offered us a lens to support the pedagogical documentation that followed our work with the children.

Part 2: Pedagogical Documentation

“Moving beyond simply an objective reporting of children’s behaviour, pedagogical documentation helps to find meaning in what children do and what they experience. It is:

- A way to value children’s experiences and include their perspectives;

- A way to make children’s learning and understanding of the world around them visible to the children themselves;

- A process for educators to co-plan with children and with families;

- A means of sharing perspectives with parents and colleagues. When families and others are invited to contribute to the documentation and share their own interpretations, it can provide even more insights that children, educators, and families can return to, reflect on, and remember in order to extend learning” (Ministry of Education, pg. 22, 2014c.)

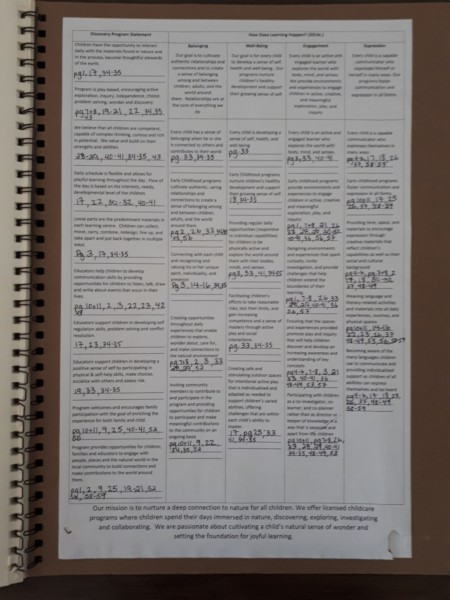

After we engaged in collaborative critical reflection with colleagues, parents, and the children we were curious about the connection with mapping and the ability to gain new perspectives of land from the sky or a “birds-eye view.” We offered the children opportunities to have regular and repeated access to the same space and used new tools such as binoculars and magnifying glasses to observe the space from new perspectives. We travelled around the space and spent time intently observing it from a variety of new vantage points such as high hills, and from further away. We engaged in a discussion about how space would look different from a tiny ant and a soaring hawk. We used a variety of resources such as google maps and go pro videos of birds flying through the Rocky Mountains to continue to build upon the children’s pre-existing knowledge about maps and perspectives.

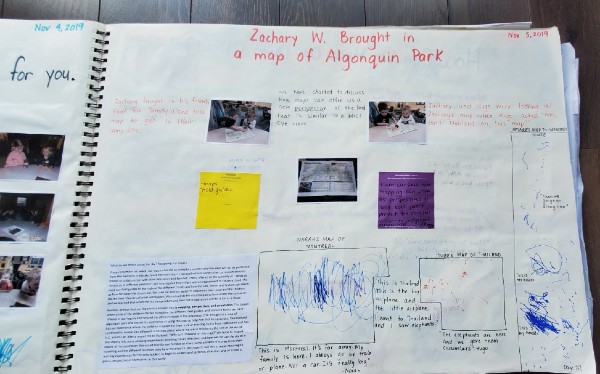

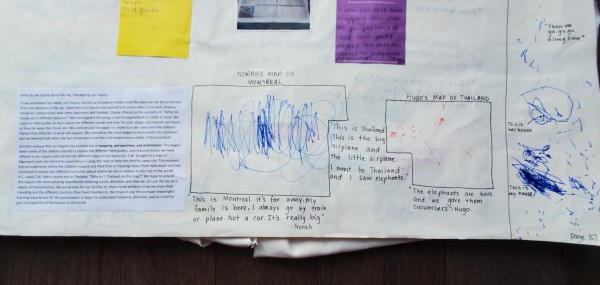

Through this process, parents supported our inquiry with ideas around experiences and resources we should investigate that could support our inquiry further. We had parents bring in books to support the children’s learning and all our families were bringing in their own maps from their travels as a family. Through this process, it offered us the chance to sit closely with specific children and hear how they have used mapping and new perspectives to understand concepts such as distance, literacy, and geographical awareness. All these learning outcomes were not nearly as valuable as the understanding and relationship I was able to foster with the families and children in our programs through this reciprocal process of sharing meaningful stories.

The children used 2-D and 3-D representations to make their experiences visible to our teaching team. This offered us new and meaningful stories to share with the families each day and strengthened the sense of community and belonging within the program for children, families, and educators.

As noted by the Ministry of Education, “In high-quality programs, the aim is to strive to establish and maintain reciprocal relationships among educators and families, and to view families as important contributors with unique knowledge, experiences and strengths. Children sense of belonging and feelings of security are also strengthened when they have opportunities to make and explore connections between home and the early childhood program. Inviting families to participate (at their comfort level) in their children’s experiences in early years programs ignites children’s interests in learning” (pg. 25, 2014c.)

Through these experiences, we were able to draw on the children’s vast understanding of the world and reflect with our team, the children, and our families to visually represent their thinking in a meaningful way that integrates a sense of belonging as well as key concepts such as literacy and numeracy development through a play-based approach. This published and very important pedagogical work served as a tool for educators, administrators, families, and children to revisit and reflect upon over the course of months. We were able to take time to slow down and notice what children were reflecting on and continue to dig deeper into their theories and continue to offer a multitude of experiences based on their reflections of their work.

Part 3: Responsive Planning

Through the evolution of this inquiry, the children have continued to use mapping to represent their thinking and ideas in 2D and 3D ways within our program. Through further collaboration with families, I reflect on the ways in which mapping can act as a tool to understand spaces over time particularly using mapping as a resource and means to understand the land we use and it’s original caretakers and gaining perspectives of the land from a perspective of the past and possible using mapping to understand the space in terms of the future as well.

I am deeply inspired by the work of Sophie Edwards and Heather Thoma with 4elements Living Arts.

“4elements is a multidisciplinary, cross-cultural, non-profit arts organization on Manitoulin Island. We investigate and integrate relationships between landscape, creativity, and community, through research, arts creation, and community cultural and economic development” (4elements, 2020).

When reflecting on their work they discuss the role that mapping has in cultivating Land-based and place-based identities for learners. In their most recent reflective resource, “Learning the Land: Creative Community Engagements” they reflect on the following insights,

- “Mapping is an age-old tool. Most cultures map the land, although not all cultures have used paper. Sometimes the land is mapped through stories passed along through generations to help remember routes, history, territory, teachings. Sometimes the land is mapped through song”

- “When maps present place and land as a static thing, the histories, natural processes and non-dominant relationships are lost”

- “Consider what cannot or usually is not included on paper maps: sounds, emotions, stories, animal tracks, change, process, wind, scents…”

(4elements Living Arts, pg. 107, 2017).

After reflecting on these insights I wonder about the broad methodology and scope that maps and mapping can encompass and versus the previously narrower image of mapping I shared before critically reflecting on my practice. I wonder about the ways we can introduce new forms of mapping that don’t involve the traditional ideas of paper and pencils that we used before. I am considering new ideas of mapping such as but is not limited to:

- Scents

- Ecologies

- Movement

- Tracks

- Sounds

- Feelings

- Temperatures

- Experiences

- Memories

- Time

- Stories

- Songs

- Plants/growth

- Music

I am reflecting on the traditional ideas and biases I shared about the ways in which learners can represent their thinking and am considering the vast possibilities that the practice of mapping can have for early childhood programs. I wonder how this can continue to evolve and the ways in which children will be able to represent their ideas in increasingly more complex and meaningful ways. I wonder about the other way’s children are mapping and I have not been attuned to it before. I wonder if everything that children are doing in their play could possibly be their own unique form of mapping or representing their theories, ideas, and values.